UK startup Babylon Health pulled app data on a critical user in order to create a press release in which it publicly attacks the UK doctor who has spent years raising patient safety concerns about the symptom triage chatbot service.

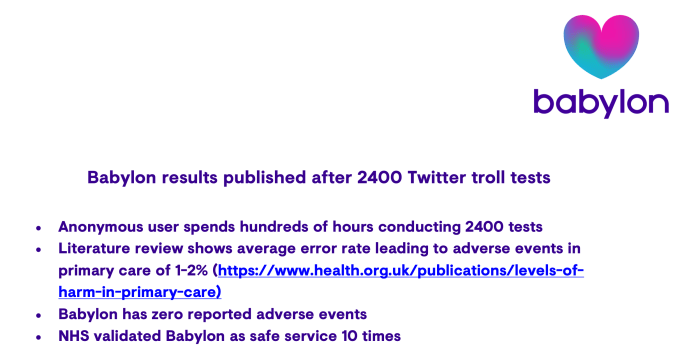

In the press release released late Monday Babylon refers to Dr David Watkins — via his Twitter handle — as a “troll” and claims he’s “targeted members of our staff, partners, clients, regulators and journalists and tweeted defamatory content about us”.

It also writes that Watkins has clocked up “hundreds of hours” and 2,400 tests of its service in a bid to discredit his safety concerns — saying he’s raised “fewer than 100 test results which he considered concerning”.

Babylon’s PR also claims that only in 20 instances did Watkins find “genuine errors in our AI”, whereas other instances are couched as ‘misrepresentations’ or “mistakes”, per an unnamed “panel of senior clinicians” which the startup’s PR says “investigated and re-validated every single one” — suggesting the error rate Watkins identified was just 0.8%.

Screengrab from Babylon’s press release which refers to to Dr Watkins’ “Twitter troll tests”

Responding to the attack in a telephone interview with TechCrunch Watkins described Babylon’s claims as “absolute nonsense” — saying, for example, he has not carried out anywhere near 2,400 tests of its service. “There are certainly not 2,400 completed triage assessments,” he told us. “Absolutely not.”

Asked how many tests he thinks he did complete Watkins suggested it’s likely to be between 800 and 900 full runs through “complete triages” (some of which, he points out, would have been repeat tests to see if the company had fixed issues he’d previously noticed).

He said he identified issues in about one in two or one in three instances of testing the bot — though in 2018 says he was finding far more problems, claiming it was “one in one” at that stage for an earlier version of the app.

Watkins suggests that to get to the 2,400 figure Babylon is likely counting instances where he was unable to complete a full triage because the service was lagging or glitchy. “They’ve manipulated data to try and discredit someone raising patient safety concerns,” he said.

“I obviously test in a fashion which is [that] I know what I’m looking for — because I’ve done this for the past three years and I’m looking for the same issues which I’ve flagged before to see have they fixed them. So trying to suggest that my testing is actually any indication of the chatbot is absurd in itself,” he added.

In another pointed attack Babylon writes Watkins has “posted over 6,000 misleading attacks” — without specifying exactly what kind of attacks it’s referring to (or where they’ve been posted).

Watkins told us he hasn’t even tweeted 6,000 times in total since joining Twitter four years ago — though he has spent three years using the platform to raise concerns about diagnosis issues with Babylon’s chatbot.

Such as this series of tweets where he shows a triage for a female patient failing to pick up a potential heart attack.

Watkins told us he has no idea what the 6,000 figure refers to, and accuses Babylon of having a culture of “trying to silence criticism” rather than engage with genuine clinician concerns.

“Not once have Babylon actually approached me and said ‘hey Dr Murphy — or Dr Watkins — what you’ve tweeted there is misleading’,” he added. “Not once.”

Instead, he said the startup has consistently taken a “dismissive approach” to the safety concerns he’s raised. “My overall concern with the way that they’ve approached this is that yet again they have taken a dismissive approach to criticism and again tried to smear and discredit the person raising concerns,” he said.

Watkins, a consultant oncologist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust — who has for several years gone by the online (Twitter) moniker of @DrMurphy11, tweeting videos of Babylon’s chatbot triage he says illustrate the bot failing to correctly identify patient presentations — made his identity public on Monday when he attended a debate at the Royal Society of Medicine.

There he gave a presentation calling for less hype and more independent verification of claims being made by Babylon as such digital systems continue elbowing their way into the healthcare space.

In the case of Babylon, the app has a major cheerleader in the current UK Secretary of State for health, Matt Hancock, who has revealed he’s a personal user of the app.

Simultaneously Hancock is pushing the National Health Service to overhaul its infrastructure to enable the plugging in of “healthtech” apps and services. So you can spot the political synergies.

Watkins argues the sector needs more of a focus on robust evidence gathering and independent testing vs mindless ministerial support and partnership ‘endorsements’ as a stand in for due diligence.

He points to the example of Theranos — the disgraced blood testing startup whose co-founder is now facing charges of fraud — saying this should provide a major red flag of the need for independent testing of ‘novel’ health product claims.

“[Over hyping of products] is a tech industry issue which unfortunately seems to have infected healthcare in a couple of situations,” he told us, referring to the startup ‘fake it til you make it’ playbook of hype marketing and scaling without waiting for external verification of heavily marketed claims.

In the case of Babylon, he argues the company has failed to back up puffy marketing with evidence of the sort of extensive clinical testing and validation which he says should be necessary for a health app that’s out in the wild being used by patients. (References to academic studies have not been stood up by providing outsiders with access to data so they can verify its claims, he also says.)

“They’ve got backing from all these people — the founders of Google DeepMind, Bupa, Samsung, Tencent, the Saudis have given them hundreds of millions and they’re a billion dollar company. They’ve got the backing of Matt Hancock. Got a deal with Wolverhampton. It all looks trustworthy,” Watkins went on. “But there is no basis for that trustworthiness. You’re basing the trustworthiness on the ability of a company to partner. And you’re making the assumption that those partners have undertaken due diligence.”

For its part Babylon claims the opposite — saying its app meets existing regulatory standards and pointing to high “patient satisfaction ratings” and a lack of reported harm by users as evidence of safety, writing in the same PR in which it lays into Watkins:

Our track record speaks for itself: our AI has been used millions of times, and not one single patient has reported any harm (a far better safety record than any other health consultation in the world). Our technology meets robust regulatory standards across five different countries, and has been validated as a safe service by the NHS on ten different occasions. In fact, when the NHS reviewed our symptom checker, Healthcheck and clinical portal, they said our method for validating them “has been completed using a robust assessment methodology to a high standard.” Patient satisfaction ratings see over 85% of our patients giving us 5 stars (and 94% giving five and four stars), and the Care Quality Commission recently rated us “Outstanding” for our leadership.

But proposing to judge the efficacy of a health-related service by a patient’s ability to complain if something goes wrong seems, at the very least, an unorthodox approach — flipping the Hippocratic oath principle of ‘first do no harm’ on its head. (Plus, speaking theoretically, someone who’s dead would literally be unable to complain — which could plug a rather large loophole in any ‘safety bar’ being claimed via such an assessment methodology.)

On the regulatory point, Watkins argues that the current UK regime is not set up to respond intelligently to a development like AI chatbots and lacks strong enforcement in this new category.

Complaints he’s filed with the MHRA (Medical and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency) have resulted in it asking Babylon to work on issues, with little or no follow up, he says.

While he notes that confidentiality clauses limit what can be disclosed by the regulator.

All of that might look like a plum opportunity for a certain kind of startup ‘disruptor’, of course.

And Babylon’s app is one of several now applying AI type technologies as a diagnostic aid in chatbot form, across several global markets. Users are typically asked to respond to questions about their symptoms and at the end of the triage process get information on what might be a possible cause. Though Babylon’s PR materials are careful to include a footnote where it caveats that its AI tools “do not provide a medical diagnosis, nor are they a substitute for a doctor”.

Yet, says Watkins, if you read certain headlines and claims made for the company’s product in the media you might be forgiven for coming away with a very different impression — and it’s this level of hype that has him worried.

Other less hype-dispensing chatbots are available, he suggests — name-checking Berlin-based Ada Health as taking a more thoughtful approach on that front.

Asked whether there are specific tests he would like to see Babylon do to stand up its hype, Watkins told us: “The starting point is getting a technology which you feel is safe to actually be in the public domain.”

Notably, the European Commission is working on risk-based regulatory framework for AI applications — including for use-cases in sectors such as healthcare — which would require such systems to be “transparent, traceable and guarantee human oversight”, as well as to use unbiased data for training their AI models.

“Because of the hyperbolic claims that have been put out there previously about Babylon that’s where there’s a big issue. How do they now roll back and make this safe? You can do that by putting in certain warnings with regards to what this should be used for,” said Watkins, raising concerns about the wording used in the app. “Because it presents itself as giving patients diagnosis and it suggests what they should do for them to come out with this disclaimer saying this isn’t giving you any healthcare information, it’s just information — it doesn’t make sense. I don’t know what a patient’s meant to think of that.”

Babylon always present themselves as very patient-facing, very patient-focused, we listen to patients, we hear their feedback. If I was a patient and I’ve got a chatbot telling me what to do and giving me a suggested diagnosis — at the same time it’s telling me ‘ignore this, don’t use it’ — what is it?” he added. “What’s its purpose?

“There are other chatbots which I think have defined that far more clearly — where they are very clear in their intent saying we’re not here to provide you with healthcare advice; we will provide you with information which you can take to your healthcare provider to allow you to have a more informed decision discussion with them. And when you put it in that context, as a patient I think that makes perfect sense. This machine is going to give me information so I can have a more informed discussion with my doctor. Fantastic. So there’s simple things which they just haven’t done. And it drives me nuts. I’m an oncologist — it shouldn’t be me doing this.”

Watkins suggested Babylon’s response to his raising “good faith” patient safety concerns is symptomatic of a deeper malaise within the culture of the company. It has also had a negative impact on him — making him into a target for parts of the rightwing media.

“What they have done, although it may not be users’ health data, they have attempted to utilize data to intimidate an identifiable individual,” he said of the company’s attack him. “As a consequence of them having this threatening approach and attempting to intimidate other parties have though let’s bundle in and attack this guy. So it’s that which is the harm which comes from it. They’ve singled out an individual as someone to attack.”

“I’m concerned that there’s clinicians in that company who, if they see this happening, they’re not going to raise concerns — because you’ll just get discredited in the organization. And that’s really dangerous in healthcare,” Watkins added. “You have to be able to speak up when you see concerns because otherwise patients are at risk of harm and things don’t change. You have to learn from error when you see it. You can’t just carry on doing the same thing again and again and again.”

Others in the medical community have been quick to criticize Babylon for targeting Watkins in such a personal manner and for revealing details about his use of its (medical) service.

As one Twitter user, Sam Gallivan — also a doctor — put it: “Can other high frequency Babylon Health users look forward to having their medical queries broadcast in a press release?”

The act certainly raises questions about Babylon’s approach to sensitive health data, if it’s accessing patient information for the purpose of trying to steamroller informed criticism.

We’ve seen similarly ugly stuff in tech before, of course — such as when Uber kept a ‘god-view’ of its ride-hailing service and used it to keep tabs on critical journalists. In that case the misuse of platform data pointed to a toxic culture problem that Uber has had to spend subsequent years sweating to turn around (including changing its CEO).

Babylon’s selective data dump on Watkins is an illustrative example of a digital service’s ability to access and shape individual data at will — pointing to the underlining power asymmetries between these data-capturing technology platforms which are gaining increasing agency over our decisions and the users who only get highly mediated, hyper controlled access to the databases they help to feed.

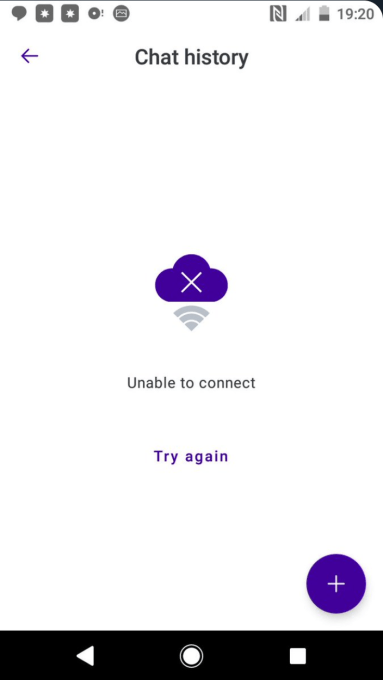

Watkins, for example, told us he is no longer able to access his query history in the Babylon app — providing a screenshot of an error screen (below) that he says he now sees when he tries to access chat history in the app. He said he does not know why he is no longer able to access his historical usage information but says he was using it as a reference — to help with further testing (and no longer can).

If it’s a bug it’s a convenient one for Babylon PR…

We contacted Babylon to ask it to respond to criticism of its attack on Watkins. The company defended its use of his app data to generate the press release — arguing that the “volume” of queries he had run means the usual data protection rules don’t apply, and further claiming it had only shared “non-personal statistical data”, even though this was attached in the PR to his Twitter identity (and therefore, since Monday, to his real name).

In a statement the Babylon spokesperson told us:

If safety related claims are made about our technology, our medical professionals are required to look into these matters to ensure the accuracy and safety of our products. In the case of the recent use data that was shared publicly, it is clear given the volume of use that this was theoretical data (forming part of an accuracy test and experiment) rather than a genuine health concern from a patient. Given the use volume and the way data was presented publicly, we felt that we needed to address accuracy and use information to reassure our users. The data shared by us was non-personal statistical data, and Babylon has complied with its data protection obligations throughout. Babylon does not publish genuine individualised user health data.

We also asked the UK’s data protection watchdog about the episode and Babylon making Watkins’ app usage public. The ICO told us: “People have the right to expect that organisations will handle their personal information responsibly and securely. If anyone is concerned about how their data has been handled, they can contact the ICO and we will look into the details.”

Babylon’s clinical innovation director, Dr Keith Grimes, attended the same Royal Society debate as Watkins this week — which was entitled Recent developments in AI and digital health 2020 and billed as a conference that will “cut through the hype around AI”.

So it looks to be no accident that their attack press release was timed to follow hard on the heels of a presentation it would have known (since at least last December) was coming that day — and in which Watkins argued where AI chatbots are concerned “validation is more important than valuation”.

Last summer Babylon announced a $550M Series C raise, at a $2BN+ valuation.

Investors in the company include Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, an unnamed U.S.-based health insurance company, Munich Re’s ERGO Fund, Kinnevik, Vostok New Ventures and DeepMind co-founder Demis Hassabis, to name a few helping to fund its marketing.

“They came with a narrative,” said Watkins of Babylon’s message to the Royal Society. “The debate wasn’t particularly instructive or constructive. And I say that purely because Babylon came with a narrative and they were going to stick to that. The narrative was to avoid any discussion about any safety concerns or the fact that there were problems and just describe it as safe.”

The clinician’s counter message to the event was to pose a question EU policymakers are just starting to consider — calling for the AI maker to show data-sets that stand up its safety claims.