As protesters flooded the streets of Iran in September after the death in custody of Mahsa Amini — a 22-year-old woman who was arrested for not wearing her hijab in accordance with the country’s strict dress code for women — videos and images of the protests spread online inside the country. Previously unheard-of acts, such as the destruction of pictures of Iran’s Supreme Leader or women removing their hijabs, were spread by smartphone video.

But then the government cracked down on internet access; and WhatsApp, Signal, Viber, Skype, and Instagram were blocked.

Now, groups are mobilizing to scale those growing walls. Most recently, a group of activists has come up with a new approach that involves Tor servers inside Iran itself, and engaging the tech community outside the country.

As that group looks to bring on more participation, its approach — using servers inside the country as a sort of ‘Trojan Horse for internet access’ — is gaining endorsement from the free-speech community at large. Currently, some 200 people are using servers run by the group of activists who devised the method; that method is now posted on Github, and the group has not tracked how many others might be using it, too.

“If Iran has segmented off its residential internet access from the rest of the world, but its servers located within the country can still access both Iranian residential IPs as well as the outside internet, then setting up servers within the country to relay traffic should work,” Bill Budington, senior staff technologist at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, told TechCrunch.

To be sure, Iranian internet users are no strangers to internet shutdowns. More than 85 million people live in Iran, with some 84% of residents having access to the internet. To suppress dissent, Iran’s regime regularly uses internet blockades and censorship to keep videos and images of the protests from reaching the population.

In 2019, when more than 100 protesters were killed during mass unrest over fuel prices, the country’s internet access was cut for 12 days, according to Amnesty International.

Details of circumvention tools and technical advice are proliferating, but the reach of censors is extensive. Even online video games — which allow players to chat — have reportedly been shut down.

For over two weeks, Iran’s three main mobile operators have blocked services for hours at a time, up to eight hours, from 4 p.m. local time daily, according to internet monitors. This means landline networks become a vital source of information.

So finding ways around those blocks has become familiar to Iranians.

Traditionally they would have turned to VPNs to stay connected.

Yet with many VPNs now getting blocked, Tor networks — which allow anonymous web browsing that can bypass internet blocks — have become especially vital for spreading video and information about the most recent protests against the regime. The Tor Project, the U.S. non-profit that maintains the Tor network, has a detailed guide in Farsi and English on how to use Tor to access the internet in Iran.

That’s why internet freedom activists are working every hour to help Iranians get back online, and are reaching out for help outside of the country to keep that information channel open for protesters.

The tech community outside Iran has come to play an important part in helping protesters get back online.

Google said in a tweet that its “teams are working to make our tools broadly available, following the newly updated U.S. sanctions applicable to communications services.”

Messaging apps Signal and WhatsApp have been working on proxies to make their services available inside Iran.

“We are working to keep our Iranian friends connected and will do anything within our technical capacity to keep our service up and running,” the Meta-owned messaging app tweeted in September.

In other efforts, Elon Musk activated his Starlink low-earth orbit satellite broadband service in Iran after the US government allowed private companies to offer internet access to the country. This followed Starlink’s activation in Ukraine after the country’s internet was disrupted by Russia’s invasion.

However, a special terminal, which includes a 20-inch satellite dish, is needed to receive the signal, making it almost impossible to ship the hardware into the locked-down country.

Now, human rights and other observers are concerned that the regime is cutting internet links and rendering VPN and proxy servers inaccessible in a chilling repeat of the 2019 protests that saw hundreds killed during the blackout.

All this has led a group of activists to take the new approach that involves Tor too, but also engages the tech community outside Iran.

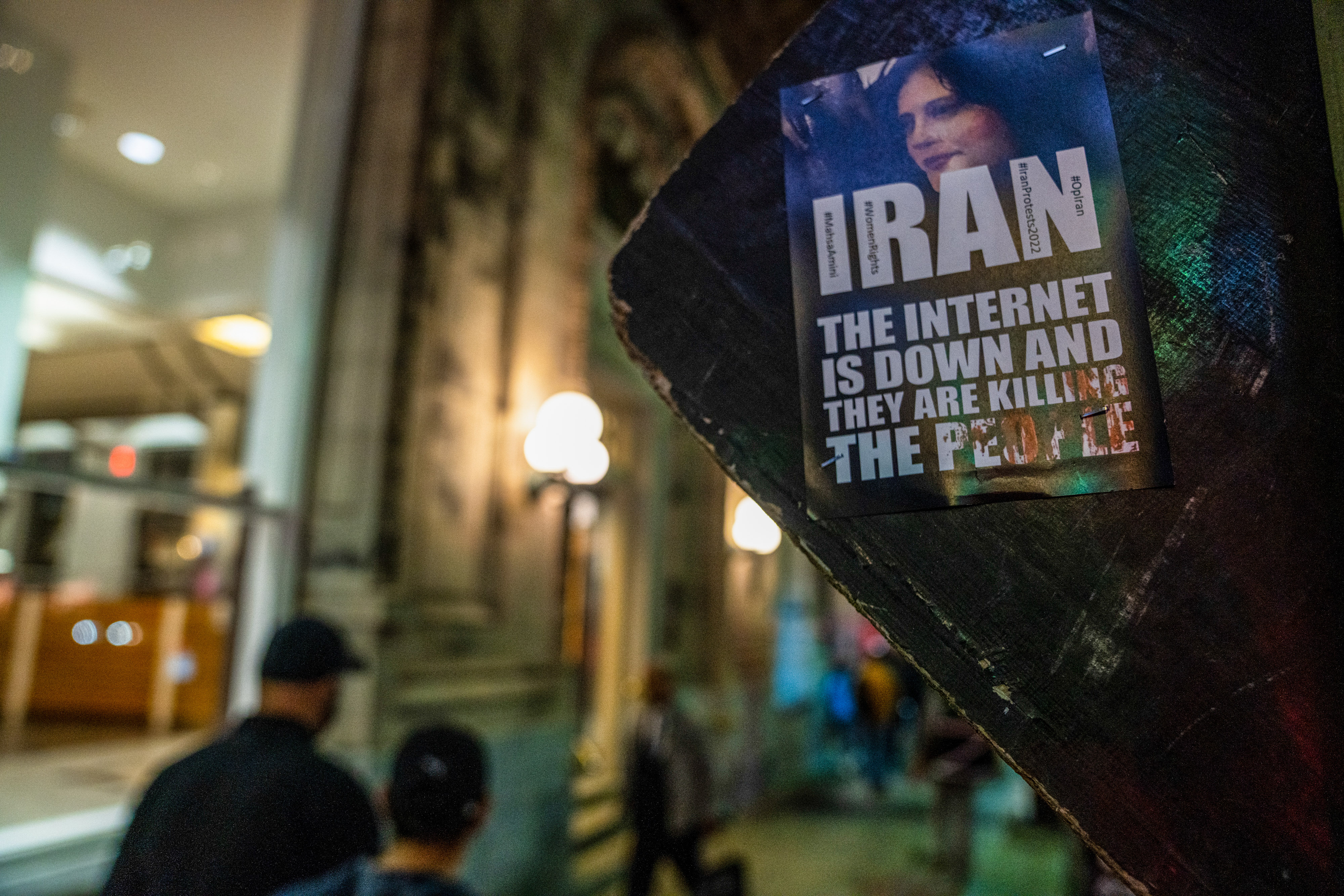

ONTARIO, CANADA – September 23, 2022: A sticker saying “Iran: The internet is down and they are killing the people” seen on the back of a road sign during the demonstration. Hundreds gathered to honour Mahsa Amini and to protest against the Iranian government in Toronto, Canada. Image Credit: Katherine Cheng/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

TechCrunch has spoken to a tech entrepreneur representing the group inside the country to get a picture of how the group of activists is working to get internet access working again to spread information about the demonstrations. (We are not publishing names to protect their safety.)

The entrepreneur said that getting access has become a “game of cat and mouse” with authorities. The Tor Project, which uses free and open-source software for enabling anonymous communication, has become a vital way around these problems. (Indeed, Tor also allows users around the world to use Snowflake, an anti-censorship system, to help users in Iran access censored websites and applications.)

Usage of the Tor anonymity network has been picking up steam as VPN blocks have increased, but even that has hit roadblocks.

“VPN services provide a free service for Iranians. The Tor Project is adding bridges, but few of these will work,” he said via an encrypted messaging app.

The regime is also now “dropping VPN connections very aggressively and you won’t stay connected to regular VPNs [with servers outside Iran] for more than a few minutes before getting disconnected,” he said.

“The government has blocked access to most non-Iranian IP addresses on residential connections (essentially a whitelist with throttled speed) and to all non-Iranian IP addresses on mobile 3G/4G data (and most people are connected to the internet through mobile data). All these services (VPNs/Tor/etc) have servers outside Iran, which is not useful,” he told me. “People cannot connect to them.”

The new approach uses servers inside Iranian data centers, which “have a full speed connection to the internet.” He and a few others are now acquiring servers in Iranian data centers, setting up a VPN server on them, and making sure that all the incoming traffic is tunneled to another server outside Iran.

“Then the Iranian VPN server connection info is shared with the people who can connect to them from any device at any time of the day,” he said. He added that the internet is almost completely shut down at nights when the protests are most intense, but connections to servers within Iran still work.

But this approach is not scalable. Iranian tech companies cannot buy many servers in the Iranian data centers as it raises too many red flags with the regime’s authorities.

“And we can’t share the connection information publicly because the connection info includes the server IP address which can be easily used by the government to identify the person who purchased it, and they can then come after us,” he said.

Instead, Iranian engineers have been in contact with members of the Tor Project to help set up bridges inside Iran.

To achieve this, he and others worked on a document titled “InternetForIran,” posted to GitHub.

This details how machines located inside Iranian data centers could be used to connect to websites and servers carrying information on the protests inside Iran, since the government has not yet blocked Internet access to these internal servers, and may not do so in fear of cutting its own access to the outside world.

The document calls on the tech industry outside Iran, including the Iranian diaspora, for help by purchasing servers.

It’s not clear how successful — or safe — the group’s proposal would be in practice.

“I don’t know how safe it is to do this and what could happen if they are caught,” one source involved with the Tor Project told me. Activists inside the country could face retribution if caught by the regime. The ongoing internet outage remains an active discussion on Tor forums.

An official spokesperson for the Tor Project did not respond to a request for comment, at publication.

Budington at the EFF believes the approach, however, fills a gap if it manages to avoid authorities’ ability to quash access. Activists appear to be “coming up with clever ways to relay traffic to the Tor network without raising red flags by routing first through the Iranian server, then out to another server outside Iran, then to the Tor network,” he told TechCrunch.

The tech entrepreneur said the method of circumventing the Internet shut-downs is in active use.

“Most people who are connected are using this method or similar methods (hopping the traffic through an Iranian server). We have roughly 200 people using our servers, but we can’t be sure of the number of people using our methods in total,” he said.

Meanwhile, the activists TechCrunch spoke to said that because of the lack of information getting out, the protests are getting “smaller and smaller every night” and the government is getting more and more confident. Authorities in Tehran recently announced that they won’t remove the restrictions on WhatsApp and Instagram unless they register companies inside Iran and abide by Iranian laws.

Activists say the methods they are working on to regain access could be crucial to aiding the protests against the dictatorial regime. “People inside Iran are not seeing the videos and information about the protests. All they see is government propaganda,” one told me. “We can give them access, but we need help.”