Software spend is becoming a prime target for cuts as it grows into a larger line item in enterprises’ budgets. According to one recent report, customers are putting 53% more toward software-as-a-service (SaaS) licensing compared to five years ago. Management has come down aggressively; 57% of IT teams told Workato in a 2022 poll that they’re under pressure to significantly reduce software spend at their organizations.

Cutting software spend is a task that’s easier said than done in companies where teams and even entire divisions rely on specific software to get their work done. The solution, Mark Ghermezian argues, is avoiding cuts in the first place — with business loans. But not just any loans — business loans specifically made out for software and infrastructure purchases.

Ghermezian is the founder of Gynger, a New York-based platform that offers companies capital to procure software and services products for their bespoke tech stacks. Gynger emerged from stealth today with $10 million in debt from Upper90 and $11.7 million in seed funding co-led by Upper90 and Vine Ventures with participation from Gradient Ventures (Google’s AI-focused venture fund), m]x[v Capital, Quiet Capital and Deciens Capital.

Ghermezian previously founded Braze, a cloud-based customer engagement platform for multichannel marketing. There, he says, he saw how difficult it was to sell software and — on the flip side — how difficult it was for buyers to purchase the software.

“Going through those pains while managing our budgets and thinking of cash flow and runway, I experienced the shortcomings of the business-to-business SaaS market firsthand,” Ghermezian told TechCrunch in an email interview. “As a founder, you raise all this money and immediately need to spend a lot of capital to build your tech stack. We wanted a way to combine software with capital to service the startup ecosystem and help them get the best software while extending and managing their cash flow.”

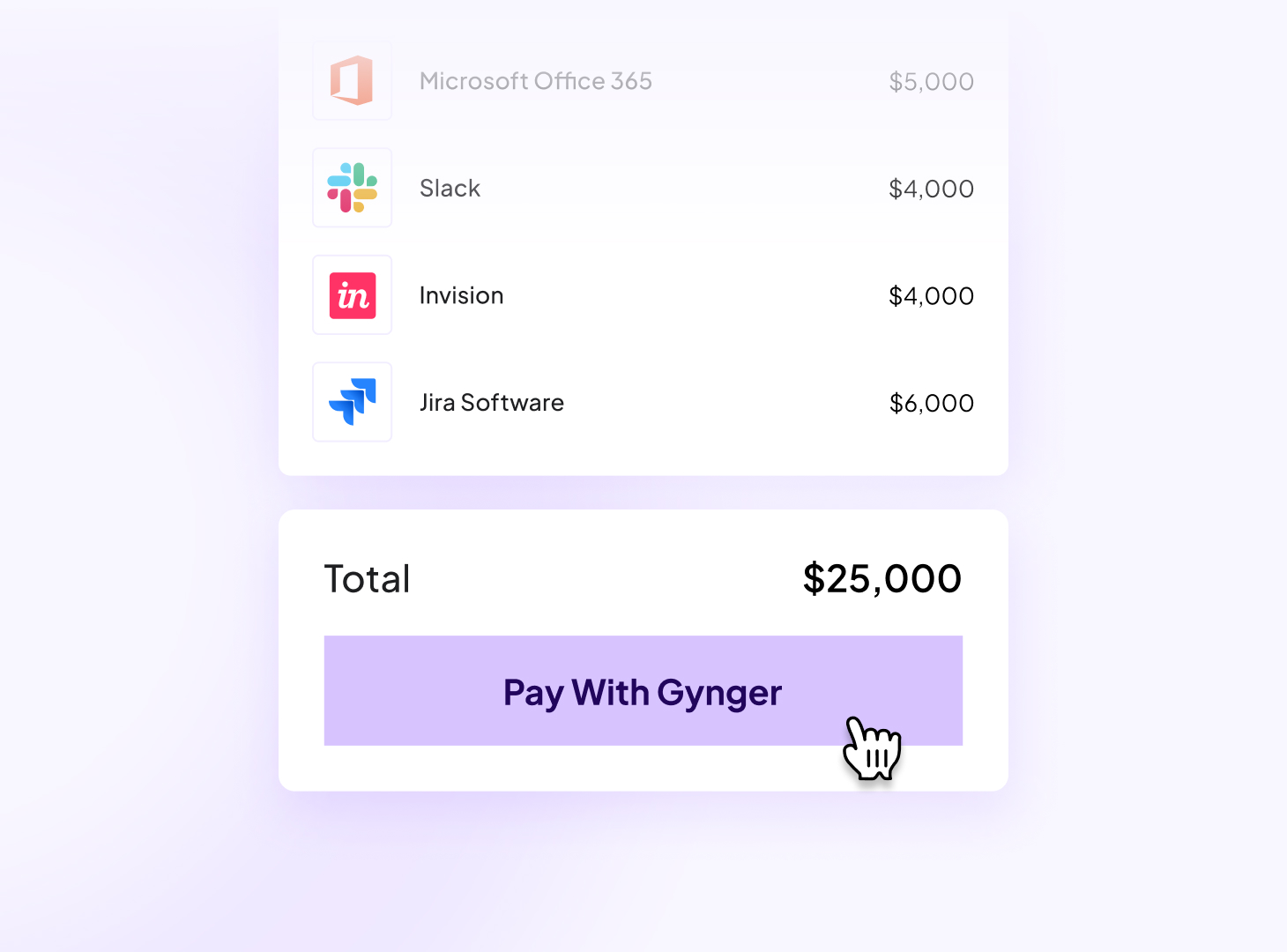

Gynger’s core product is an automated underwriting model for financing software and infrastructure purchases. The company provides a line of credit and debt financing to corporate customers, allowing them to pay their SaaS bills upfront while paying back Gynger later. (Ghermezian says that the debt Gynger raised will be used to finance these, although Gynger can — and has — loaned off its balance sheet.)

Image Credits: Gynger.io

Ghermezian lists what he sees as the top benefits of Gynger’s platform, including giving customers access to upfront payment discounts from vendors and the ability to spread out lump sum payments over the course of three to 12 months. Gynger also provides a unified dashboard for SaaS expenses that consolidates them into a single monthly payment.

There’s some customizability with Gynger. Customers can choose to pay vendors the full year upfront in exchange for a discount or spread out existing bills, for example, and decide which contracts they want Gynger to finance on their behalves. Ghermezian says that Gynger’s decisioning algorithm looks at cash, burn rate and revenue to determine how much capital a company is eligible for.

The alterative financing market has exploded as macroeconomic headwinds spur companies to seek out nondilutive forms of capital. Ghermezian sees Gynger competing closely with fintechs like Pipe and Capchase, both of which provide businesses funding outside of equity and venture debt. But he notes that many loaners focus on purchasing a company’s receivables (i.e. funds owed goods and services) and lending against their annual recurring revenue. While Gynger considers revenue in making its loan decisions, it doesn’t require a company to have it.

“Companies of all sizes can benefit from Gynger, but we’ve seen particular success with pre-Series B companies,” Ghermezian said. “With Gynger, any company of any size can access non-dilutive capital, purchase the software and infrastructure they need to run their business and pay on their terms.

Lending to a company without revenue might sound risky. And Gynger’s website pitches the platform as a way for vendors to upsell customers by using flexible financing as an incentive for larger purchases, which also seems risk-seeking.

But Gradient Ventures’ Darian Shirazi said he believes that Gynger is taking a measured approach to doling out capital.

“The per-seat annual billing software model is evolving and we believe Gynger is offering new ways for companies to buy software that best suits their financial situation,” Shirazi added in a statement. “Many have attempted to innovate on the underwriting model for software financing, but the real multi-billion dollar opportunity is in offering a myriad of payment and financing workflows depending on customer need. Gynger is revolutionizing how customers pay for and purchase software and we’re thrilled to partner with them.”

In any case — setting the risks aside — lending for software spend seems like a decently safe business model bet, given that worldwide IT spending is expected to grow 4% to $4.5 trillion by the end of 2022, according to Gartner. That’s certainly a large and growing addressable market.

To date, Ghermezian says that Gynger has financed SaaS contracts as small as $1,000 to as high as $1 million from vendors including Airtable, Google Cloud Platform, Amazon Web Services, Slack and Zoom. He declined to reveal Gynger’s revenue, but claimed that the 13-person company is “super healthy” in terms of cash flow.